For many years, we have discussed ‘the individual as the point of integration for data about them’, and that statement is hard-wired into the MyData Principles. But what that means in practice has been less than clear. With COVID-19 as an inspiration/ driver, we have had to dig into that in more detail; this paper summarises how we believe ‘individuals as a point of integration’ can be delivered at scale using the W3C standard for Decentralised Identity’.

COVID-19 as a Driver for Action and Change

There are not many upsides to the COVID-19 experience, but one may emerge from the rubble as a positive boost for those working in the MyData community. COVID-19 has given us a giant, data-intense use case, the time to study it in detail, and the incentive to move at pace.

For a long time, many of us in the ‘human-centric data’ community have talked about ‘the individual as the point of integration of data about themselves’; this is the first post I recall on that from 2007. Evidence would suggest that turning that excellent theory into reality is easier said than done. Let’s face it, we are all now well accustomed to the whole sign-up, sign-in ‘notice and consent’ based model that dominates The Internet, and which places organisations firmly at the center of the current personal data eco-system.

To be an integration point for data, according to Wikipedia,

an entity will combine data from multiple sources into a unified view.

When the entity in question is an individual, the challenge has always been how to enable the individual to have a digital integration point that is not actually run for them by another entity. That ‘entity other than the individual’ problem is mainly around perceived ‘lock-in’; and because genuine data portability has not yet emerged at scale, individuals will not integrate many streams and/ or large data volumes inside relationships and technologies that they do not genuinely control. There is also the ‘chicken and egg’ issue that larger organisations who could easily give individuals access to data they could integrate in their own unified view, do not do so as no standardized way to make that work technically has emerged as yet. We have attempted to mitigate this in a range of ways over the years either through hardware-based approaches, entities that were structurally on the side of the individual, ‘Coloured button (data portability) projects’, and separation of a data store from data use. None as yet has achieved mass-market adoption. Prior to COVID-19, our next community attempt to address this was to be in the MyData Operators work-stream in which we will seek to address this challenge via certification, improved data portability and ultimately interoperability.

Then, along came COVID-19; a life episode impacting pretty much every person on the planet with medical, economic and societal implications. Life episodes have long been known in the design community as areas not well served by the current silo-ed, organisation-centric model. They are always hot-beds of interaction and transaction, and critically require people to integrate many different aspects of life in order to get stuff done. The underlying problem is that when people’s support services are silo-ed, and their needs are not, then there is a gap that only the individual can fill; which normally means putting in the time and effort to knit together solutions.

Then, along came COVID-19; a life episode impacting pretty much every person on the planet with medical, economic and societal implications.

The COVID-19 life episode demonstrates the above; in fact, it is a more extreme example than most in that for those not critically ill and/ or hospitalized and/ (i.e. 99.5% of the population) they are unable to access and use their core medical record to log COVID-19 symptoms. Hackathons and app developers attempted to fill that gap by providing a range of apps, but in truth, there is now a very clear case for all individuals having abasic, digital mechanism to access and augment a basic health record that is co-managed with their healthcare authority. In future pandemics, and in more mundane circumstances, personal health records are one of the main data sources that individuals would benefit from being able to integrate into their unified view. Had that been the case in COVID-19, or statistical analyses would be much more accurate and useful than they are at present.

The MyData Commons Prototype

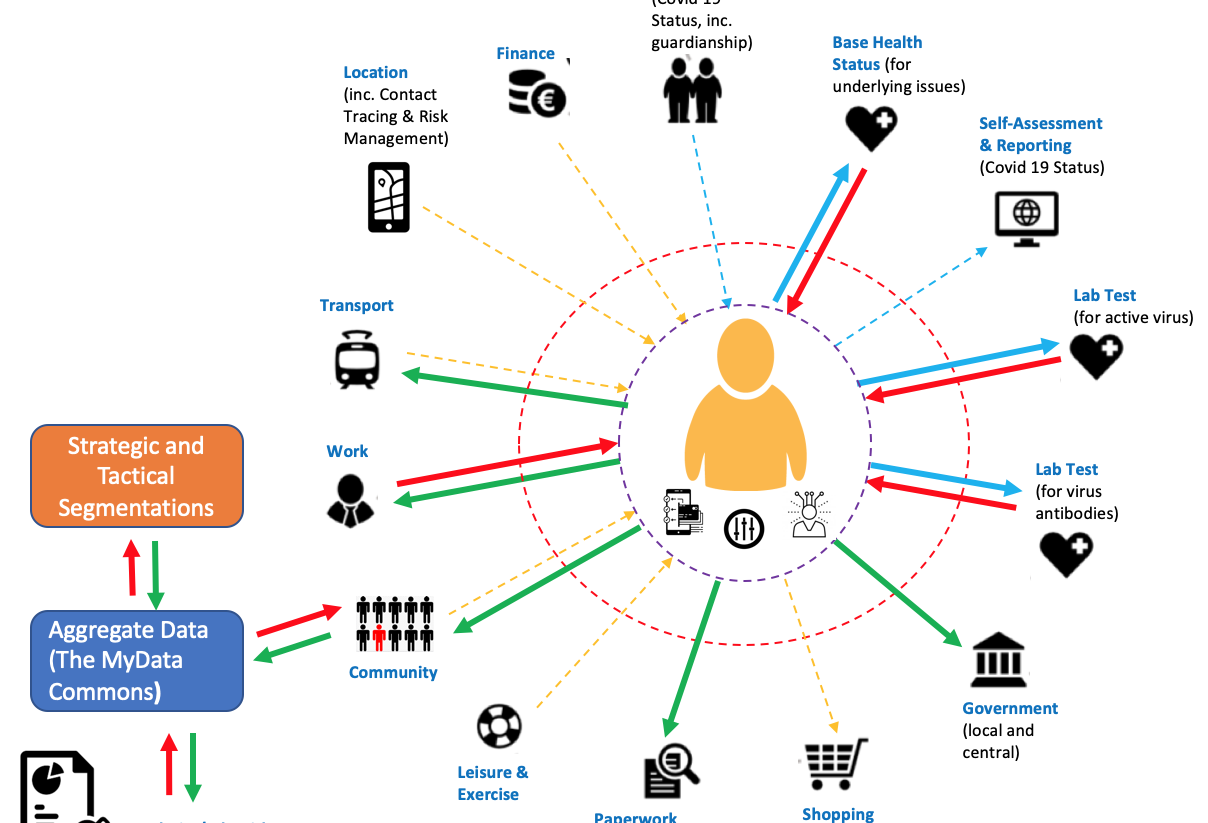

The above is what led the team working on a ‘MyData Commons prototype’ to ask the question ‘so what precisely would it take to make an individual the point of integration in a COVID-19 context?’. We came up with the following re-interpretation of the MyData main visual graphic as our guiding light. Whilst all of the data areas and the relationships within them are important, those with the thicker arrows felt like the more immediate areas to work on and build into our prototype.

The areas we wished to drill into to truly understand the individual as the point of integration became:

- Can an individual access and use their core medical record at their health authority, and integrate relevant parts of that into their own unified view (aka COVID-19 Profile)

- Can an individual request a test for active virus (PCR test) and integrate the result into their own unified view?

- Can an individual request a test for prior virus exposure (Immunity test) and integrate the result into their own unified view?

- Can an individual share the results of their PCR and/ or immunity test (i.e. their unified view) in controlled ways with their local and central government organisations, their employer, their transport providers and their wider community should they need to?

- Can an individual contribute appropriate data from their unified view to the aggregate ‘MyData Commons data-set in order to aid the wider community, and in doing so better understand their own wider context as regards COVID-19 and the actions they need to take?

Clearly, the above capabilities require an individual to have data management tools in some shape or form on their side; precisely which tools are indeed the heart of this paper.

Very quickly we settled on looking deeper into tools and capabilities based on decentralised identity.

Very quickly we settled on looking deeper into tools and capabilities based on decentralised identity. That is not to discount tools based on other technologies; it was more than when one realizes that some of the data to be shared would be sensitive medical data, then the reality is that the only way to do that at real scale is to first pass the data from a health care provider or lab to the individual, and only when formally under the domain of the individual can it be passed elsewhere with the overt permission of the individual. The alternate model would a consent-based approach where the individual would consent to their healthcare provider passing the relevant data to one or multiple other entities. We felt that to be sub-optimal if we could find a way to genuinely have the individual as the point of integration and genuinely enable multiple parties to co-manage the data they are either the subject, the source or the user of. We also noted early on the potential of ‘verified claims’, a technology built on top of decentralised identity, to be part of this mix.

Decentralised Identity

What, therefore, is a decentralised identity; how does it work, and what does it enable? Firstly, it is important to note that decentralised Identifiers (DIDs) are an emerging global technology standard being evolved at W3C. But from the individual perspective, the underlying plumbing is not the top priority; ‘what does it do?’ is more important for adoption and use. To quote from the specification:

Decentralised identifiers (DIDs) are a new type of identifier that enables verifiable, decentralised digital identity. A DID identifies any subject (e.g., a person, organisation, thing, data model, abstract entity, etc.) that the controller of the DID decides that it identifies. These new identifiers are designed to enable the controller of a DID to prove control over it and to be implemented independently of any centralised registry, identity provider, or certificate authority.

One could think of a decentralised identifier as a bit like a mobile phone number, or a bank account/ sort code combination. The former is an identity that is required to make things happen when it comes to mobile communications; the latter is required to make things happen when it comes to managing money. To extrapolate from there, one could see a decentralised identifier as a number that is required to make things happen as regards managing my data.

To be more specific then, when it comes to moving data about me around, my DID is the actual point of integration (and that DID points to a specific human who controls it). Actually, there are likely multiple my DIDs involved but we’ll come back to that another day; the principle remains the same.

There are other useful analogies relating to DIDs and the mobile phone number or banking identities:

- I most likely get one from an ‘operator’ who sets it up for me and provides services based on it.

- I use it to get stuff done (in this case move data backwards and forward and to manage permissions) with other entities that also use DIDs.

- I can get more than one if I like, for different purposes; but need ways to manage that complexity.

- If I decide to change providers, I should be able to do so without losing data or functionality; because all providers are running with the same standards-based approach.

- People can find me via that number; but only if I have decided to be visible and accessible, and they have the necessary permission.

- I am not bound to one centralised register to have access to services.

Personal Data Banking

And when one connects a DID to data, the analogy of ‘my bank account number as the way to access and use my bank’ becomes more useful still. If we think of an individual managing their data in not dissimilar ways to how they manage their money in a current bank account, then consider:

- There is a banking code that enables and enforces the fiduciary or neutral relationship between a provider and the individuals they provide services to.

- The rules of engagement are clear, fully transparent and underpinned by regulation

- access to the COVID-19 databank, and the individuals ‘account’ can be through multiple channels, initially online and via mobile apps; but over time potentially via contact centres and physical locations

- Assets (data) are micro-managed with full referential integrity and provenance of the assets a mandatory feature (i.e. there is a full audit log of every data transaction just as there is with bank statements and mobile phone call/ use logs)

- Multiple parties, with the permission of the individual, can put assets(data) into the personal account with the DID as the integration point for doing so

- Multiple parties can, with the permission of the individual, receive assets (data) from the personal account, with the DID as the integration and control point for doing so

- Data portability is enabled by a mandatory account switching mechanism that means service providers can be substituted out and in via a standard methodology

- Data interoperability is a given because of a shared core data model for accounts and transactions.

In the COVID-19 scenario then; how would such a databank work? Here is the user experience we worked up in the MyData Commons project.

Step 1: An individual signs up with a MyData Operator, in this case, the JLINC reference implementation; this gives them their own DID. It also gives them a basic databank, the ability to read, understand and sign information-sharing agreements; and where a signed agreement is in place, the ability to interact with other parties who also have DIDs.

Step 2: An organisation that wishes to establish a trustworthy data-sharing relationship with this individual sets up their own point of integration on the operator service. This gives them a DID, a basic databank, the ability to read, understand and sign information-sharing agreements; and where a signed agreement is in place, the ability to interact with other parties who also have DIDs.

Step 3: Either party can initiate an information-sharing request, which invites the other party to review and, should they wish to, digitally sign the proposed information-sharing agreement. Either party can suggest what data should be in scope; the individual is always in the driving seat as to whether they do share a specific data attribute or not. DIDs are used in the signing mechanism and recorded in the audit log. To carry on the banking analogy, this ceremony could be thought of as the data equivalent of direct debit (i.e. permission to transact under conditions defined in the agreement and enabled by the system). To make that real, when an individual engages with a COVID-19 testing lab, that is part of the ecosystem they are already co-managing a data-set in the analogue world; we are now talking about the mechanism to do the same in the digital world. The shared data-set has, at its core, the following attributes:

- This individual (DID)This testing lab (DID)

- Test type

- Test date and time

- Test ID

- Test result (e.g. antibodies found, prior virus exposure confirmed)

- Degree of confidence that the result is accurate

The user interface through which data fields to be co-managed is shown below.

Another, different organisation (e.g. an employer) necessarily requires a different data-set to be co-managed; in that employer case, it might be:

- This individual (DID)

- This organisation/ employer (DID)

- Employee role

- Employee role (keyworker or not)

- Employee start date

- Employee termination date

Each organisation has its own interface covering the data-set they have agreed to co-manage with each individual. The individual is unique in having a unified view across all of his/her data-sharing relationships. Only the individual can present the illustrative unified view below to whoever needs to see it.

I (DID) am employed by this organisation, in this role, which is a keyworker role; and I have a COVID-19 medical status of ‘prior virus exposure confirmed’.

The user interface for the above is shown below – an individual managing multiple organisational data sharing relationships from the one interface.

The visual below illustrates the individual having integrated data from two separate sources into their unified view, and then presenting that for use by a further party. Note that this scenario also delivers data portability in a human-centric way; the individual is always in the flow when data about them is ported either to them to stay with the individual for their own use or to then be ported on to another party.

The individual is always in the flow when data about them is ported either to them to stay with the individual for their own use or to then be ported on to another party.

All of the above co-management, data sharing and data portability happen in real-time; the DID to DID connection is a very different model to the ‘notice and consent’ model we have lived with for the last 25 years, and which has reached the end of its ability to scale.

Conclusion

To summarize, if we believe that the definition of an individual acting as the point of integration for data about them is that they can pull in data from two or more services into a unified view, and then present that to a third party; then that has been delivered in the MyData Commons prototype. Decentralised identities (DIDs) are critical in delivering that, and appear to be critical to the evolution of the MyData Operators network.

Join the #decentralised-identity Slack channel and help us set up the decentralised identity thematic group!

Author

Iain Henderson

CRM Lead for JLINC Labs,

Project Lead on DIDs for Kids, MyData Scotland Hub

iain(at)jlinclabs.com

@iainh1