The EU Commission published the long-awaited Data Act on February 23, 2022. This is a progressive legislative proposal to increase access to data for the users of connected products suchs as Iot devices and related services. It is a significant move towards realising the MyData principle of portability, access, and re-use as well as the principle of interoperability. It will potentially also move the needle towards the shift from formal to actionable rights in terms of the right of data portability. With such a progressive agenda, the proposal will certainly also face significant opposition and counter-lobbying from those who stand to benefit from the status quo.

This new proposal should not be confused with the Data Governance Act (DGA) -proposal (our analyses here and here) published by the Commission in late 2019. From the MyData perspective, these two similarly named proposals complement each other nicely. The DGA clarifies the role of data intermediaries such as MyData operators. The Data Act, on the other hand, strengthens the user (individuals or organisations using the connected products) access to and portability of data generated using connected products.

Ideally, the future human-centric infrastructure for personal data could rely on strong data access and portability rights (via well-formed APIs) and trustworthy data intermediaries that serve the people when executing those rights.

The GDPR defines the right to data portability for personal data, but it’s practical implementation and usefulness have some serious shortcomings that the Data Act aims to fix. The data portability Article 20 of the GDPR covers ‘data provided by the data subject’, but it does not specify if this requires the data subject’s active behaviour or also applies to situations where a service “observes” the data subject’s behaviour in a passive manner. So far, there has been little progress of organisations making ‘machine readable’ data available as mandated under GDPR. This is likely because the regulation remains ambiguous on what “data provided by the data subject” specifically means, and so it leaves the door open for organisations to say: ‘we’re not sure what that means, so we can’t do it’.

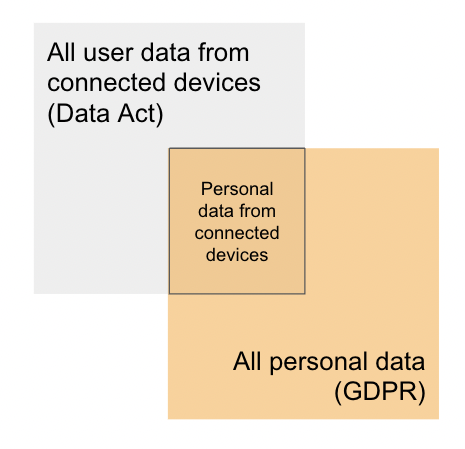

The Data Act is like the GDPR Art 20 on steroids: data portability made actionable and concrete. It covers data generated by using a connected product or a related service, irrespective of whether it is personal data as defined in the GDPR or not, irrespective of whether it is actively provided by the data subject or merely observed, and irrespective of the legal basis of processing it.

On the other hand, it is good to remember that while the Data Act also covers non-personal data, it only focuses on data generated by the use of physical connected products and related services. Hence, all not all web services are in scope.

The Data Act also covers interoperability related to data spaces and minimum requirements to smart contracts for data sharing, easier switching between cloud service providers, and business-to-government data sharing, among other topics. On these topics, good analyses have been published by Sitra and Bertelmanns Stiftung.

MyData Global is supportive of the Data Act proposal as a whole. And even in a good proposal, there is always room for some improvements, and here are our top picks to make the Data Act live up to its potential to create more human-centric, fair, sustainable, and prosperous digital societies for Europe and beyond:

1# Terminology and definitions

2# Data intermediaries and API’s

3# Compensation for making data available

4# Technology neutrality regarding the data sharing contracts

1# Terminology and definitions

The terminology of data holder and data recipient should be aligned with the GDPR and the DGA to create a precise language across the key regulations covering data transactions. In the DGA, there is ‘data holder’, which was after the joint opinion of the European Data Protection Authorities made separate from ‘data subject’. The Data Act only has the data holder (no data subject), and the wording is slightly different from what is in the DGA.

Our proposal is to include a definition of ‘data subject’ with reference to the GDPR and to amend the definition of ‘data holder’ to make reference to the DGA.

Another alignment is needed on the terminology regarding the ‘data users’ or ‘datarecipients’. The DGA has ‘data user’, and the Data Act has ‘recipient’.

Our proposal is to amend the Data Act to use ‘data user’ with reference to the DGA.

Also, the Data Act should include ‘data intermediation service’ and ‘operator of data spaces’ in the definitions with the content aligned with the DGA. Currently, Article 28 (Essential requirements regarding interoperability) clearly states that the operators of data spaces shall comply with interoperability requirements. Still, data space or the operator of data space is not defined.

Our proposal is to include definitions of ‘data intermediation service’ with reference to the DGA and a definition of ‘operator of a data space’.

[gdlr_styled_box content_color=”#000000″ background_color=”#f3f3f3″ corner_color=”#f3f3f3″]

Proposed amended and added text for Article 2 Definitions

(5a NEW) ‘data subject’ means data subject as referred to in point (1) of Article 4 of Regulation (EU) 2016/679;

(6 AMENDED) ‘data holder’ means data holder as referred to in point (5) of Article 2 of [DGA];

(7 AMENDED) ‘data user’ means data user as referred to in point (6) of Article 2 of [DGA];

(21 NEW) ‘data intermediation service’ means data intermediation service as referred to in point (2c) of Article 2 of [DGA];

(22 NEW) ‘operator of a data space’ <DEFINITION TO BE DEVELOPED COLLABORATIVELY WITH THE KEY STAKEHOLDERS DEVELOPING DATA SPACES>

[/gdlr_styled_box]

2# Data intermediaries and APIs

The data intermediaries defined in the DGA are not referenced in the articles of the Data Act (but there is one mention of them in recital 35). It is essential to ensure that data holders also fulfil the data requests when those requests come via notified data intermediaries acting on behalf of the user.

Article 5 of the Data Act refers to “a party acting on behalf of a user”, which can be interpreted to cover also data intermediaries. It would be best to explicitly include the reference to data intermediaries to make the distinction between:

a) data intermediaries conveying the data request on behalf of a user, but not using the data

b) data recipients conveying the data request on behalf of a user, and also being the data recipient

Another important improvement in Article 5 would be to make a clear requirement for providing the data via well-formed APIs. One of the key implementation and usefulness challenges of the data portability clause in the GDPR (Art 20) is that it does not set precise requirements for providing the data to be ported via APIs. It is essential to the success of the Data Act that this challenge of the GDPR is directly and decisively tackled by the explicit requirement of APIs.

[gdlr_styled_box content_color=”#000000″ background_color=”#f3f3f3″ corner_color=”#f3f3f3″]

Proposed amended and added text for Article 5 Right to share data with third parties

(1) Upon request by a user–directly, via a data intermediation service, or via the intended data user–the data holder shall make available the data generated by the use of a product or related service to a third party, without undue delay, free of charge to the user, of the same quality as is available to the data holder, via a well-formed API and, where applicable, continuously and in real-time.

[/gdlr_styled_box]

3# Compensation for making data available

Articles 4 and 9 may create confusion about the possibility for data holders to ask for compensation for making the data available.

Article 4 (and the same is repeated in Art. 5) says that the users shall get the data free of charge. Article 9 states that any compensation agreed between a data holder and a data recipient for making data available shall be reasonable. The idea seems to be that the compensations would be charged from the third parties (data recipients), but the users would get the data for free.

This separation may become dysfunctional in the (many) cases where the user wants to port the data to a third party service. In these cases, the user has the right to get the data for free, but on the other hand, the data holder has the right to charge the third party service. In the case of personal data stores (PDS), for example, the user is the recipient (allowed to have the data for free), but technically the PDS service may be offered by a third party (subject to charges).

4# Technology neutrality regarding the data sharing contracts

Article 29 requires the operators of data spaces to “enable the interoperability of smart contracts within their services”, and Article 30 sets requirements regarding smart contracts for data sharing.

The definition of smart contract in the Data Act is technical and specific: “‘smart contract’ means a computer program stored in an electronic ledger system wherein the outcome of the execution of the program is recorded on the electronic ledger.”

It is a valid aim to improve smart contracts’ interoperability and tame the ills of bad distributed ledger implementations. However, there are also functional non-ledger-based technologies for data sharing contracts, which would benefit from interoperability and minimum requirements.

Article 30 only refers to data sharing in the title of the article. Beyond that the requirement seem to be general for smart contracts.

[gdlr_styled_box content_color=”#000000″ background_color=”#f3f3f3″ corner_color=”#f3f3f3″]

Proposed amended and added text for Article 28 Essential requirements regarding interoperability

(d) the means to enable the interoperability of smart contracts for data sharing within their services and activities shall be provided.

[/gdlr_styled_box]