November 19 was a big day for EU data policy. It saw the release of the European Data Union Strategy (now reframed to pursue data for AI), the Digital Simplification Omnibus (proposing simplifications and reforms across multiple acts and directives), and a Digital Fitness Check call for evidence (to review how the entire body of regulation on digital “affects and supports the competitiveness objective of the EU”). These reform proposals are important because of their signalling power to companies and regulators around the world, and because Europe is so uniquely equipped to develop data ecosystems that actually serve people.

Real concerns

It is precisely because of their importance that there has been such significant dismay from civil society and the research community, raising alarms about watering down core protections in the interest of “competitiveness” (widely understood as focused on increasing businesses’’ access to data and lowering their administrative hurdles). These concerns are real. It would be a mistake to remove the AI Act disclosure requirement for companies that exempt themselves from high-risk categorisation. It would be a step backwards for the GDPR to allow companies to define what counts as personal data based on their own capabilities.

Many have described this as Europe prioritising profit over people and planet. But that’s not quite right, because it’s not a zero-sum game. The imperative to bolster European competitiveness and strategic autonomy is based on deep analysis (e.g., Letta, Draghi, and Niinistö) and wide consensus in the face of profound geopolitical uncertainty. Strengthening Europe’s global competitiveness is important, but we need to design for the competitive markets we want to emerge, and simply rolling back requirements for businesses is no silver bullet.

Don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater

The real problem with the proposed reforms is that they are an attempt to beat global superpowers at their own game, a tactic sure to fail: lowering administrative burdens with brute force and narrowing a fundamentally flawed definition of personal data as the only basis for people to claim sovereignty over data about themselves. Instead, Europe should leverage what Europe does best. This means finding the spaces in the global data value chains where it can lead, and to build market dynamics on core values: human dignity and the rights of individuals. Flawed as it still is, GDPR remains the flagship of Europe’s global regulatory leadership in recent decades, and only by doubling down on a commitment to the values of protecting and empowering people can Europe hope to compete and thrive in the emerging global digital economy.

The link between people and AI is illustrative of the above. The Data Union Strategy focuses on mobilising data for innovation and AI, with a significant reliance on the production of data through Common European Data Spaces. But despite referencing “high-quality” data 17 times in its 21 pages, the strategy does not define the conditions required to produce high-quality data. One of those conditions must certainly revolve around the people from whom almost all data is somehow sourced, through their activity online and in data spaces (whether directly or indirectly). Establishing governance systems for people to be and to feel empowered over their data and how it is used is a turnkey priority for creating reliable, valid, and safe data to fuel Europe’s Data Labs and AI factories.

Like so much in the omnibus and data strategy, this potential isn’t excluded. There’s nothing in the Strategy that prohibits governance mechanisms designed to foster trust-based data generation by and with people, for and in data spaces. But failing to invest in this dynamic carries a tremendous opportunity cost. It misses the long-term opportunity to invest in trust-based quality of data, it misses the opportunity to strengthen people’s engagement with the digital single market, and it misses the opportunity to foster European competitive innovation anchored in data portability and human-centric business and market behaviour.

Doubling down on European values is Europe’s best bet for both competitiveness and autonomy. Our Roadmap for Europe suggests 20 concrete actions to start that process.

Bright spots

There are also several improvements proposed in the Digital Omnibus and Data Union Strategy. Consolidation of data regulations into a single Data Act can be a good first step towards coherence, independent of substantive adjustments. The proposed reforms to the ePrivacy Directive in order to reduce cookie banner bloat are also welcome, and open significant opportunities for users to cast and enforce their privacy preferences, and for digital advertisers to adopt more human-centric practices. As usual, though, the devil is in the details, and the details have yet to be laid out in full.

What’s next?

Negotiations and debates on the digital omnibus in the European Parliament have already begun, and will continue towards adoption in mid-2026. MyData will continue to engage with policymakers and regulators in Brussels and European Union Member States to advocate for embedding a values-based approach and human-centricity in the negotiation of the omnibus, the execution of the Strategy, and elaboration of related reforms. This will build on the concrete interventions we have been advocating for this year. Our Human-centric Roadmap for Europe urged the Commission to take concrete steps to create market incentives for human-centric business practices and to embed trust into the AI ecosystem through 20 concrete actions. Our People-First Playbook identified 17 repair interventions that could strengthen the benefits and outcomes for people using Europe’s digital single market.

To build support for these concrete actions, we advance four high-level messages about how anchoring European regulation in European values can strengthen Europe’s global competitiveness and strategic autonomy. Below we argue that Europe should (1) build a trust foundation for AI, (2) build digital sovereignty on personal data sovereignty, (3) build competitiveness on people’s empowerment, and (4) abandon a too narrow focus on “personal data” as the only data that matters for people.

1. Build data quality on trust, not exploitation

High-quality data doesn’t come from scraping, harvesting, or the performative checking of consent boxes. These practices damage trust, fostering digital apathy and system fatigue. This limits the quality and scope of data that people are willing to offer, and creates perverse incentives to sabotage data systems. We see the consequences of this all across today’s internet, but Europe can differentiate itself by designing data spaces as a trust engine for data labs and AI factories. Every data space where individual people or their data are involved, managing their health, mobility, tourism, or energy data, there is an opportunity to empower people with control, and build the trust on which the quality of data is created. Every data space that traffics in data about people without involving them there is a chance to do this. Governance mechanisms that deliberately empower people can make data spaces a trust engine for European AI. For details, see the Human-centric Roadmap for Europe, pgs 12-14.

2. Build Europe’s digital sovereignty on personal data sovereignty, not (just) the cloud

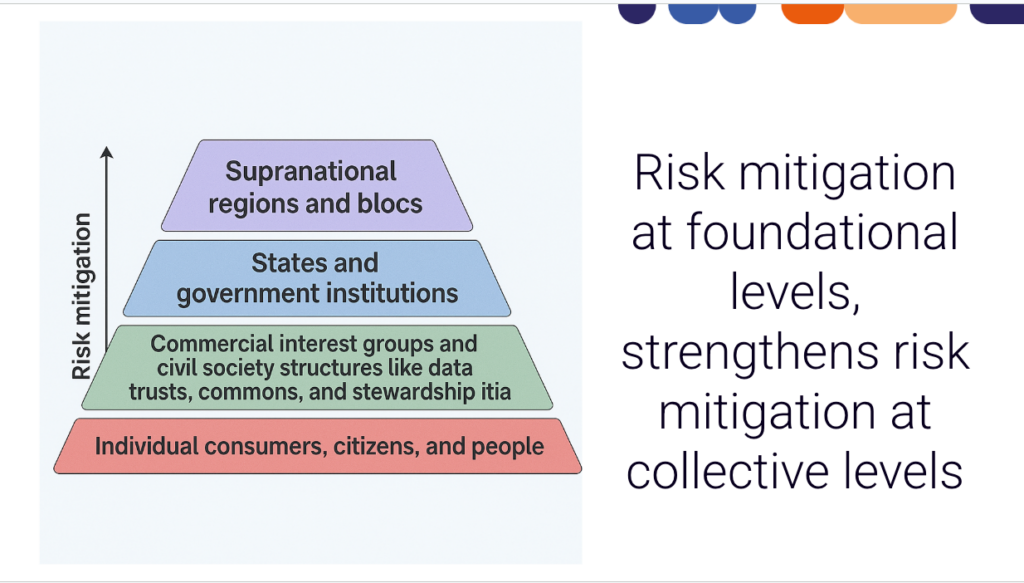

Europe’s digital sovereignty should build on the data sovereignty of individual people and groups. Decentralised and federated data control and storage at the edge gives individuals meaningful agency over the data about themselves, and creates a sovereignty stack that starts at the human layer and scales upward. This form of sovereignty is harder to copy, harder to capture, and more aligned with Europe’s values than any purely technical or geopolitical strategy. For details, see this slide deck and the Human-centric Roadmap for Europe, pgs 15-17.

3. Build competition and innovation on empowerment, not exclusion

Europe’s long-term competitive advantage lies in markets that reward businesses and public agencies that prioritise interoperability, transparency, and individual agency for people. Europe has a unique opportunity to demonstrate how strengthening the literacy, agency, and control of citizens and consumers can create more sustainable business models and citizen engagement. This means making data mobility real, enabling new market entrants to build on shared infrastructures, and encouraging innovation focused on restructuring how value is created, captured, and shared between data subjects and data controllers. Compliance regimes can be simplified by privileging data controllers that adopt these models, decreasing burdens for the right kinds of businesses, while fostering a more vibrant, diverse, and future-proof digital economy. For details, see the Human-centric Roadmap for Europe, pgs 11-12.

4. Regulate control over data about people, not personal data

Europe’s data regulation remains balanced on a brittle and shifting distinction between personal and non-personal data. This distinction is increasingly meaningless in a world where non-identifiable data can be so easily reidentified, and where so much data that might not identify any one of us directly can have such profound implications for how we live our lives. The real issue is not whether a dataset contains an identifier, or whether a data controller claims that they can or cannot identify individual people, but how data about people and their interactions shapes opportunities, risks, and rights. In a world where health outcomes, credit scoring, mobility planning, public services, and AI-driven systems all rely on “non-personal” data that infers things about us, the harms and benefits extend far beyond what GDPR classifies as “personal.” As definitions of personal data are harmonised across EU regulations, Europe should avoid privileging this specific category of data as the only type that should be subject to individuals’ rights and claims. For more information, see the think piece In This Together, pgs 4-11.

*Feature photo by Christian Lue on Unsplash.