Patients – and citizens – should be in charge of their data to ensure correctness, completeness and accuracy, optimizing continuity of care from their providers and effective generation of datasets for public health innovation & policy-making.

In a previous blog post arguing for an individual-centric European Health Data Space (EHDS), we presented the comments from the MyData community on the EHDS draft regulation issued in May 2022. The regulation is now final, and our focus is on how we could make it happen, building on the MyData principles. This blog post is the first one in a series where we will address data quality, tools to enhance it, data security, data “solidarity” and emerging platform solutions based on MyData operators reference model, digital wallet, intelligent digital assistant and data governance.

One way of finding out the general opinion on a subject is to ask ChatGPT and Google Gemini. When asking ”why should citizens and patients be in control of their health data”, the reasons these models both put forward are benefits such as privacy and security, empowerment, improvement of care quality and healthcare outcomes, support to innovation and research, and financial benefits. In addition, ChatGPT mentions data accuracy, trust and transparency, and equal access to information.

All these arguments are valid. Conventional wisdom in the global healthcare sector is that they can be satisfied by the growing number of patient portals provided by hospitals, Electronic Health Records (EHRs) and by the emerging National Contact Centres for Digital Health (NCDPH) proposed in the EHDS Regulation to pool the data of individual citizens collected by healthcare organisations.

So everything seems fine! Why should I worry about my health data? Hospitals and authorities are taking care of it..right? But is that enough? Unfortunately, the answer is NO. It’s not good enough for patients, it’s not good enough for providers, it’s not good enough for researchers and policy-makers. The major reason for concern is data quality; ChatGPT partially identified this by referring to data accuracy, i.e., data integrity, correctness, and completeness of records.

The painful reality about health data

- Health data is scattered across multiple systems. Around 40% is managed and stored in one or more hospital medical record systems; while most citizens in Europe go to the same hospital throughout their life, they may be referred to a specialized hospital for a specific episode of care, or they may move and change hospitals. In other regions, like the US, citizens and patients in average move 11,7 times1 during their lifetime.

The other 60% of health data is included in GP systems, home care, vaccination centers, dispensaries, clinical trials and safety monitoring systems from pharmaceutical companies, and increasingly in wearable devices used in the context of telemedicine. - Health data is heterogeneous; it comes in a variety of formats and standards (most often proprietary, HL7, openEHR, SNOMED, LOINC, ICD and in the pharmaceutical sector, CDISC, MEDDRA). In addition, the same standard may have different extensions and interpretations across borders that limit semantic interoperability. In other words, health data is neither interoperable nor reusable without further, often cumbersome, processing called data curation.

- Health data is not readily processable. Up to 80% is in narrative format (±40% in full narrative documents, another ±40% in unstructured data with small chunks of text that may include acronyms and abbreviations (e.g “140 mg 3 tpd” meaning “140 mg 3 times per day”)

- Health data is not well documented. Most health information systems in place in hospitals are old with ancient designs and technologies (Epic – 1979; Cerner/ChipSoft – 1976; McKesson – 1960; MEDITECH – 1969; Allscripts – 1986; SAP IS-H – early 90s and being retired in 2030; many proprietary systems from the 90s), with limited metadata and requirement on reuse. The underlying data stores are not documented sufficiently to enable smooth extraction and quality enhancement.

- Health data is redundant and error-prone. Research indicates that up to 30% of information in a health record is redundant2 (often due to the practice of copy and paste by junior staff) and can be the source of inconsistencies. In a survey3 of 29.656 patients, 25% found errors in their record, 40% of these were considered as very serious: in short, 1 in 10 patient records contain very serious errors that can negatively impact the patient but also health decision-making4. As an example in Europe, 1 person out of 1 million dies every day from a medication error; one of the acknowledged reasons is missing or incorrect information in the patient record.

- Assessing quality of health data at source is not scalable and expensive: as long as data is heterogeneous and not computer processable, quality checks can only be implemented in a fragmented way and usually too cumbersome to deploy.

As a consequence health data which are ubiquitous, are underused for prevention, treatment, research or public health decision making. A case in point is the ability to predict pancreatic cancer5, notoriously one of the hardest cancers to diagnose in early stages and thus one of the most fatal.

Health data make up more than 30% of the world’s data assets, and yet less than 3% of that data are used for decision-making in the public interest. Hence 29% of the world’s data assets of public interest are unused.

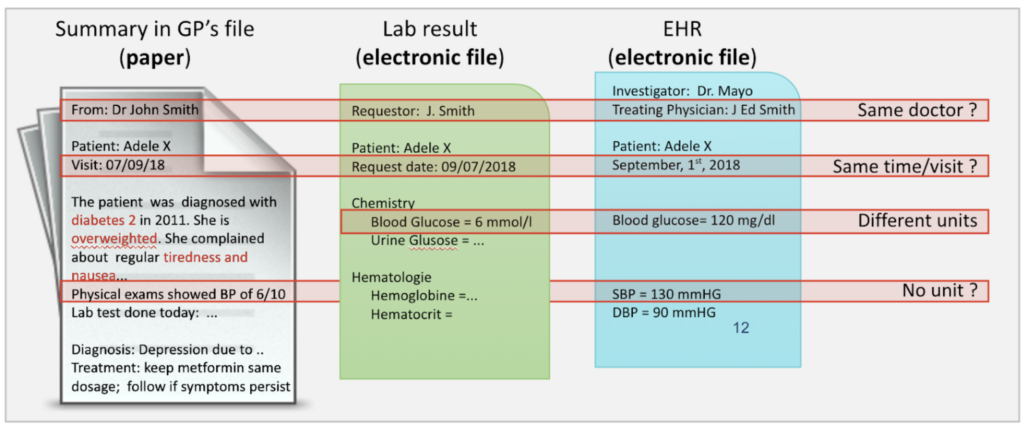

To make the problems more real, let us take a very simple example described in the figure below with 3 different data sources:

- paper from the GP,

- electronic files from a laboratory and

- electronic files from the hospital Electronic Health Record (EHR).

This represents a pool of disparate health information that doctors would access on their computer, browsing through different files; they read the narrative document to understand its content, assume that the doctor in charge registered with different names is the same, manage the transformation of units or deduct certain units, ..

We can infer that the way we manage health data today is not acceptable!

- It is not good enough for patients (and citizens) because their health records are disparate with questionable data quality, and they are not sure they will receive the appropriate quality of care.

- It is not good enough for frontline providers. All too often, they have neither the time nor the tools needed to take an overall view of their patients’ health. And they have to make decisions on the basis of these fragmented and potentially incorrect data.

As the patient’s problems increase, the size of records increases, with more documents to consult; the assessment of a patient’s medical condition becomes more time-consuming, while there is a shortage of providers who are then forced to focus on the patient’s latest problem. Providers may miss important information about the patient’s history, leading to redundancies (requesting data that is already available) or medical errors with complications that could have been avoided. In addition, the stress on providers increases, with risk of burnout. - It is not good enough for researchers and policy-makers. Because of the lack of interoperability of source data, they have to carry out tedious and recurrent curation of the source data. In addition, because of the risk of low quality in the source data, they must extract and process a wider sample of subjects. Quality at population level might then be achieved, yet the time to curate and ensure quality are consequent and might be better used to increase quality at the patient level.

Impact of messy data on patients and citizens

What is the impact on low quality of data on citizens and patients? Let us look at two fictional characters; they are, on purpose, extreme to help clarify the proposed approach.

John is a healthy guy with a university degree. He is in his mid 40s, with 2 children, and is a widower. He had a short nervous breakdown when his wife died 5 years ago from a painful cancer; he had to be treated by a psychiatrist. He completely recovered and has never seen a physician since then.

He is highly successful in his career with potential to move up.

John is a “citizen6”. He is not really interested in his health data; he is not aware of the content of data privacy laws and he is concerned that one day his employer may gain access to his health record and realises that he needed to have support from a psychiatrist. However, he knows that he, or his beloved children, may become sick and require access to good quality of care. As he heard that by 2030, there will be a shortage of physicians in all care specialties and it will be even more important to have any of his – or his children’s – health data in a form easily accessible by the providers he trusts, he realizes that he may have to take full responsibility for the health records of his family as he is the only person who is truly interested to do so. However, he has no idea how to do this.

Peter is the brother of John, but has only high school education, mainly because of his health history. He is in mid 40s, no children, happily married. He had leukaemia at the age of 7 with heavy chemotherapy. He is cured from the leukaemia but the chemotherapy had consequences and he suffers from infertility and renal insufficiency with one kidney transplant at the age of 15 with regular follow-up and medications. In addition, he was diagnosed a few weeks ago with type 1 diabetes.

Peter works as an employee in a company; he needs to take regular time off to go to the hospital for checkups. Because of his long medical history, he has a large health record with data coming from several hospitals and his GP. In his record, he found out that there is missing information and procedures recorded with incorrect results. He is particularly concerned about the result of a CT-SCAN report mentioning that both kidneys are normal.

Peter is a “patient”: he is a heavy consumer of care services and his health data are paramount to ensure quality of care. He has no issue in sharing his health data to support research and public health but he wants to make sure that his own data are of the needed quality and easily accessible by any of his frontline providers. This is particularly important for him, in the context of the newly diagnosed diabetes as he will be treated by another team of providers who are not knowledgeable of his medical history.

Finally, he is afraid to travel beyond his local area of care in case of problems he is not sure the frontline physicians in the place where he travels will have access to the appropriate information. Having access to his international patient summary (IPS) is a good start, but not enough. He has so many discharge summaries and lab reports that he knows how difficult it will be for a physician to have a complete view of his problem.

Peter wants to improve the quality of his health care record as he knows that it is critical to ensure continuity of care and quality of care. He is the only one who knows that there are errors in his records and he wants to correct them but has no idea how to do it. And he is the only one who is truly interested in improving his personal dossier; he is also the only one who can spend the time or ask another person to help him. But he has no idea where to start and where to get support as he does not understand much about IT and data.

Health organisations have limited capability and capacity to improve data quality

While healthcare expenditure on average is 9.2% of GDP7 (± 10% in Europe, 17% in the US), the budget available for each individual health organisation to improve their legacy systems – and hire dedicated staff to increase the quality of data – is low.

IT budgets within healthcare are still a low percentage, between 2 to 5%8, as their core function is direct patient care, which involves staffing, medication, and medical equipment. IT plays a vital supporting role, but it’s not the central focus of spending.

Without profound changes in the healthcare system, there does not seem much hope that quality of individual patient data will improve in the near future.

What if patients could be in charge of their health data

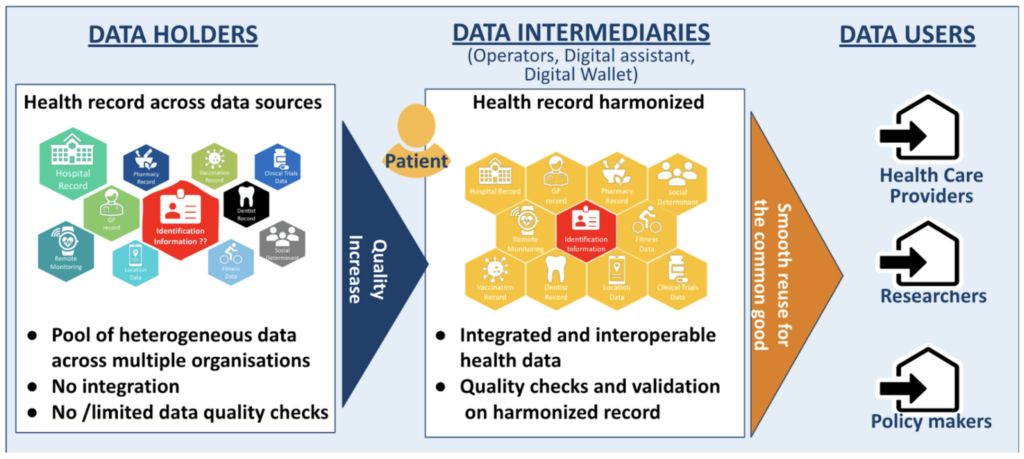

Let us assume we can put in place an infrastructure including

- governance based on data intermediary organisations, as regulated in the EU Data Governance Act Regulations or by international frameworks such as the OECD Recommendation on Health Data Governance (2016)9;

- technology platforms with open protocols following the MyData operators reference model10, augmented with a Digital Wallet and an Intelligent Digital Assistant supporting patients to enhance the quality of their health record at their level of health and digital literacy11, and helping providers to navigate through potentially complex dossiers, and an AI forecasting tool12 to support prevention and personalized medicine.

- people, such as expert data scientists/ data curators that would be available to patients and citizens in case they cannot manage by themselves to control their health record.

If we could provide Peter with such an infrastructure (technology, governance, people) to support him in transforming his data into a harmonized data set and in checking their quality to correct errors and redundancies and identify potential missing data, he would be the first one to spend the needed time to ensure his dossier is in order. John might not have a pressing need but will do it in due time, for him and for his children. And overall health data management would be vastly improved across all stakeholders, at societal level.

This solution, with a high quality health record at each single patient, is a new and efficient paradigm in health data management.

- It is beneficial for patients and citizens as their record can be clean, accurate, complete, readily accessible by all (with their consent).

- It is beneficial for frontline providers as the Intelligent Digital Assistant helps them to acquire a comprehensive view of the patient with limited effort.

- It is beneficial for researchers and policy-makers; when they need data they can request different data intermediaries organisations who will manage consent of the patients they serve and provide data in the format needed; there is no need to manage consent, there is no need to curate the data.

We need to provide citizens and patients with an infrastructure (governance, technology, people) that allows them – or their deputies – to PROACTIVELY control their data to increase their quality, first for the benefits of their frontline health care providers, and second for the benefits of researchers and policy makers.

In the next blog posts will describe in more detail the MyData vision on the needed infrastructure. Stay tuned !

How Can I Find Out More and Participate?

- Join MyData Global as a member

- Join MyData Slack and discussions at the #health-data channel

- Follow MyData Global LinkedIn and X feeds

- Subscribe to our newsletter

- Sign the MyData Declaration

Acknowledgements. The ideas described in this paper were inspired by the principles of human-centric use of personal data, the DNA of the MyData Global organisation, and by the very intense discussions on the potential use of MyData operators framework within the #health-data community. Patient analysis is the result of discussion with DataForPatients and the patient consultants involved in the AIDAVA Horizon Europe project. Eric Sutherland from OECD and Prof Dipak Kalra from The European Institute for Innovation through Health Data, provided insightful comments.

This post is authored by Isabelle de Zegher (MD, MSc), currently serving as the vice-chair of MyData Global’s Steering Committee, Berrin Serdar from Cloudprivacylabs, Lal Chandran from iGrant.io and Jim StClair from Myligo.

1 https://www.movebuddha.com/blog/moving-industry-statistics/

2 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3599108/

3 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7284300

4 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9983735

5 https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(24)00690-1/abstract

6 In this context, the word citizen should be understood as any natural person.

7 https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/7a7afb35-en/1/3/7/1/index.html?itemId=/content/publication/7a7afb35-en&_csp_=6cf33e24b6584414b81774026d82a571&itemIGO=oecd&itemContentType=book

8 As a comparison, IT budgets in finances are reaching double-digit percentages (easily over 10%).

9 https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/health-data-governance.htm

10 https://mydata.org/publication/understanding-mydata-operators

11 https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2024.1365501

12 https://erictopol.substack.com/p/medical-forecasting