To benefit all stakeholders and ensure green digital innovation, implementation of the European Health Data Space must focus on individual health records.

As a citizen and a patient, would you agree to share your data to support the “common good”? Absolutely yes, would say most of us. As a patient with serious medical conditions, would you still answer wholeheartedly, yes? When you know that your data are spread across several health care providers and organisations, in a heterogenous, non-comparable format, and when you do not have any support to organise and improve this data and ensure your treating physician has easy access to them, you might wonder what can be done better. The emerging European Health Data Space (EHDS) regulation aims to alleviate the situation. However, this requires a paradigm shift from the currently proposed population-centric approach to a truly individual-centric implementation.

The proposed approach for EHDS implementation is population-centric

The EHDS draft regulation was published by the European Commission in May 2022 for public consultation. It is the first regulation describing a sector-specific data space, under the umbrella of the European Data Strategy published in November 2019. Comments on the draft EHDS regulation were provided by the European Parliament in November 2023, and by the European Council in December 2023; officials from the Commission hope the regulation could be finally approved in Q2 2024. Several projects – including TEHDAS and EHDS2 pilot – are working on recommendations for implementation and carrying out pilots.

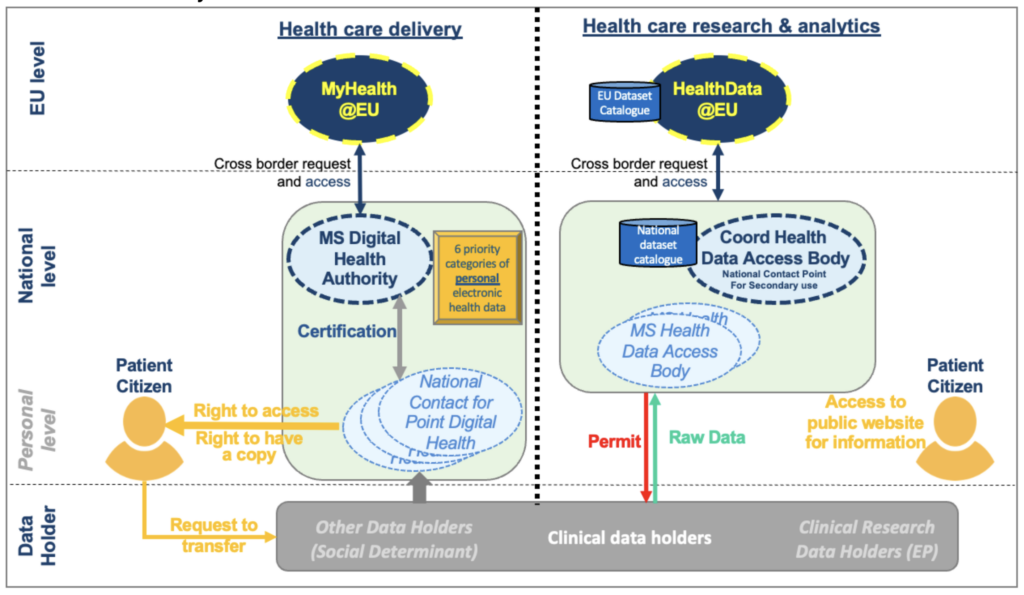

The graphic below provides our high-level summary of the 140+ pages of regulation. It shows that the regulation splits the healthcare world in two: healthcare delivery and healthcare research and analytics.

Healthcare delivery includes data that is generated within clinical care (hospital, general practitioner, telemedicine with medical devices and personal apps) and data related to social determinants of health (socio-economic context, environment). All this data will be centralised within National Contact Points for Digital Health (NCPDH) acting as a gateway for EU citizens and their treating physicians to access their data. NCDPHs are coordinated by a Member State Digital Health Authority, which is expected to enforce the implementation of six categories of personal health data for cross-border exchange: patient summary, discharge letters, lab reports, e-prescriptions, e-dispensations, and imaging reports. On the health research and analytics side, certified Health Data Access Bodies (HDAB) will have a “permit” to access citizens’ data — while respecting data privacy per GDPR regulation — to support the “common good” i.e. clinical research and policy making.

This proposal means that all of my health data will be centralised in one place – a NCDPH. As a patient, I can have access to this data and request a copy. Furthermore, I and any physician in Europe will have access to my six most critical datasets in a standardised format. In addition, my data can be used to support the “common good” and I am able to learn how it is being used by accessing a public website where I can opt out if I do not want to contribute.

This is indeed a huge progress that will benefit EU citizens and increase their freedom of movement across Europe while smoothing access to data for researchers and authorities. However, this hides important shortcomings.

Firstly, there are limited benefits for me as an individual patient in daily care where my treating physicians need a personal longitudinal health record (PLHR) integrating all my data. Medical records are based on heterogeneous data, spread in different organisations, and different systems, and collected in different forms; they can be structured based on different standards, in full narrative or in semi-structured format. In addition, health data is often incomplete (missing procedures), with inconsistencies (same parameter having a different value at the same time across different data sources) and errors (incorrect date of a procedure or worse, incorrect encoding of a diagnosis). Transformation of this messy data into a high-quality, interoperable and reusable format is a complex task. The EHDS is concentrating on extracting six types of data, not on delivering a complete personal and comprehensive medical record.

“I personally tried to correct a — fortunately small — mistake in my medical record: the result of a cardiac test that never took place. I could not change it in my hospital app, so I called the hospital at least twice and I was promised that this would get corrected. Nothing happened. The EHDS implementation will not help me with this. When I requested a copy of my medical record to organise it, I received 52 MB of PDF documents in 2 files; EHDS will only help me to get more PDFs — or equivalent — from more organisations, but will not help me to improve the quality and readability of my messy medical data.”

Secondly, the generation of secondary datasets for research and analytics will remain a burdensome, costly, recurrent process. As mentioned before, health data are not readily reusable. To deliver a secondary dataset, expert curators working within the Health Data Access Bodies (HDAB), must extract a subset of pseudonymised data from data sources, integrate and transform this data into the format required for the analysis. As the GDPR regulation does not permit linkage of personal data without a legal basis, and individual consent is difficult to obtain, health data are most often not linked, and the curated data provides only a partial view of the individual patients. Finally, as each secondary use may require slightly different datasets, an individual’s data may be curated several times, resulting in massive and unnecessary duplication of effort.

Thirdly, the EHDS may become a contributor to additional GreenHouse Gas (GHG) effects. After painstakingly generating secondary datasets, HDABs will not be prone to delete them even though the probability of reuse is low. In addition, they might be forced to keep these datasets for liability purposes. Data centres account for more than 2.5% of all Greenhouse Gas Emissions (GHGE) in 2022 and are targeted to rise to 14% by 20401. 30% of the world’s data volume is generated by healthcare [ref], rising to 36% by 2025. More than 90% of the data stored in data centres are not used more than once.

The EHDS should be individual-centric

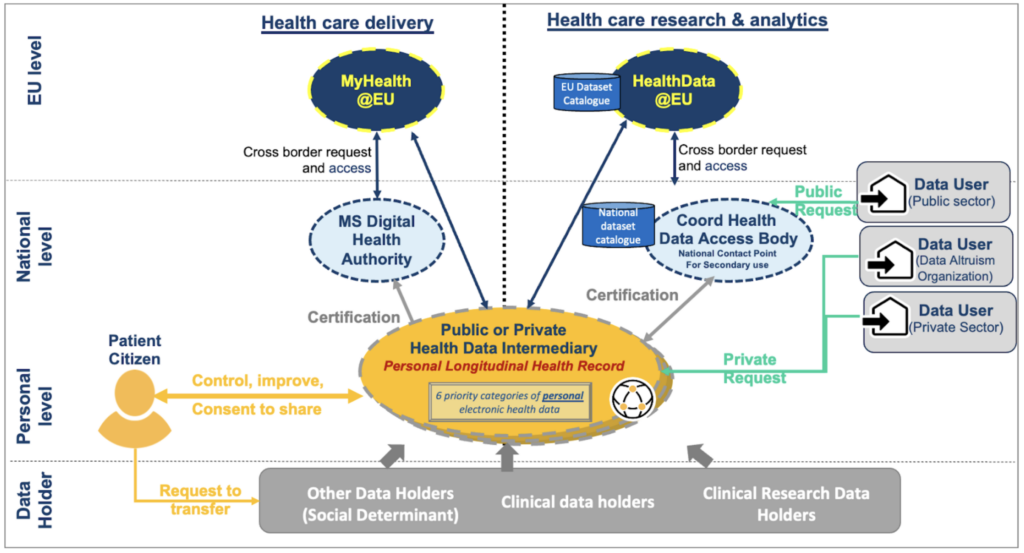

In order to mitigate the shortcomings, there is a need to explore an alternative approach: an individual-centric EHDS that meets the needs of both healthcare delivery and research. At the core of this approach is the maintenance of each individual’s personal longitudinal health record (PLHR), introduced above, integrating all their personal data, into an interoperable and reusable record.

An individual-centric model for the EHDS would presume that my personal longitudinal health records (PLHR) will be managed by my trusted local Health Data Intermediary, which I can choose to manage my health data assets in the same way I can choose a bank to manage my financial assets. My Health Data Intermediary will be tasked to gather all my personal data, across different systems and organisations and help me to clean (i.e., curate) this data into a standard format; it will also generate from my record the six priority categories of data and insert them into my health digital wallet that I could use across Europe. Finally, it will support me in sharing my data with different data using services with differential consent based on my preferences. For instance, “always share for the common good”, “ask me if this is for private use for research”, “never if this is for commercial purposes”.

The individual-centric approach will solve the three major issues mentioned above.

First, as a patient, I will have full control of my entire health record, and as a delegated caretaker, potentially the one from my loved ones, my children and grandchildren. I will be able to integrate all my health data, including the increasing amount of data I capture personally through health and wellness apps and medical devices. Provided I have the appropriate digital tools, I could also improve the quality of my health records supporting its transformation into an interoperable and reusable format. Alternatively, I can ask a third person I trust, more competent than I am, to do so for me. All processing of data will produce an audit trail to support data lineage, and a data quality label. As a result, I will be able to provide this high-quality health record to my treating physician; he/she will not have to go through multiple files to understand my health condition, and can spend that time instead providing the best care. I will be able to generate the six priority categories data, whenever relevant. Finally, by being empowered to manage my health data and draw insights, this individual-centric approach will likely help me improve my health behaviour and result in better health over my lifetime.

Secondly, data users — public health HDABs and private organisations— will have access to high-quality data that can be integrated across consenting patients, and programmatically transformed into the needed format for research. Secondary datasets can be generated just in time, with limited manual curation; they will include not just the data needed but also a label of quality derived from the different patient records they are extracted from. They will also include metadata — including the program used to generate them — supporting re-generation of this dataset if needed.

Thirdly, while data sources must be kept and stored securely within the data holders who collected them originally; secondary datasets, derived from these data sources, can be deleted as they can be reproduced by rerunning the program that generated them, on the version of the data sources at the time on which the original data set was generated.

Is this just a dream? No. Many Health Data Intermediaries exist today and it’s up to us to demand a better health data ecosystem and to justify its value. However, this requires overcoming several challenges.

- Deployment of private or public data intermediation service organisations – as regulated by the EU’s Data Governance Act – certified in the same way as NCDPHs and HDABs, and deployed at large scale in Europe with sustainable financial models. This could include funding by national public health authorities for minimal services, and additional contributions by citizens for extended services. The PGO (Personal Health Environment) in the Netherlands is an attempt in that direction.

- Implementation of digital identification of individual patients – based on eIDAS, supported by a digital wallet usable for both online and offline public and private services across the EU and most particularly for identification purposes and for the exchange of personal data. The EUDI pilots of such wallets could be extended to health care.

- Availability of automated data cleaning/curation services within Health Data Intermediaries, supporting every citizen – at their level of health and digital literacy – to increase the quality of their messy, heterogeneous health data and to transform them into a clean, interoperable longitudinal health record. This is probably the biggest remaining challenge, which requires more research. Work has started already, showing there is potential (see the project I have the pleasure to co-coordinate www.aidava.eu).

The road ahead is not easy but difficulties can be overcome. It will require courage, innovation, hard work and mostly a paradigm shift from a population-centric view of health and the EHDS, to a true individual-centric implementation that will benefit ALL stakeholders, including our planet.

Time to roll out our sleeves!

How Can I Find Out More and Participate?

- Join MyData Global as a member

- Join MyData Slack and discussions at the health-data channel

- Follow MyData Global LinkedIn and X feeds

- Subscribe to our newsletter

- Sign the MyData Declaration

1 H. Lavi, “Measuring greenhouse gas emissions in data centres: the environmental impact of cloud computing.

Acknowledgements. The ideas described in this paper were inspired by the principles of human-centric use of personal data, the DNA of the MyData Global organisation, and by the very intense discussions on the MyData operators framework coordinated by Joss Langford, Koen de Jong and Antti ’Jogi’ Poikola. The EHDS analysis is the result of collaboration with other MyData fellows – Sille Sepp, Jan Leindals, Mikael Rinnetmäki, Lal Chandran and Fredrik Lindén – who contributed to MyData comment to the public consultation on EHDS.

This post is authored by Isabelle de Zegher (MD, MSc), currently serving as the vice-chair of MyData Global’s Steering Committee.