We believe that 3 pillars are required in Healthcare to support a FAIR data economy: Data Quality, Data Interoperability and Data Solidarity. Two previous blogs describe the first 2 pillars.

This blog is focusing on the third pillar: Data Solidarity.

In a previous blog on health data quality we described the importance to provide citizens and patients with an infrastructure (governance, technology, people) that enable them – or their deputies – to PROACTIVELY control their data to increase their quality, for the benefits of their frontline health care providers, as well as researchers and policymakers.

In another recent blog with Professor Celebi from the University of Maastricht, we explained the need to develop a different approach to solve health data interoperability, building on the lessons learned from the AIDAVA Horizon Project. We describe a 10-years structured roadmap that should help to reach health data interoperability and reusability at affordable cost, provided there is support from policymakers and active engagement of citizens.

This blog is focusing on a third component of a human-driven fair data economy: health data sharing. In a world where increased pandemic risks require data-driven evidence to regularly adapt public health guidelines, and where there is major innovation potential expected from data-trained AI solutions, effective data sharing is critical to increase the amount of available data.

Over-sharing or under-sharing of data can be detrimental [1], but so can sharing of poor quality data. Sharing heterogeneous data requires costly transformation to make it easily reusable. Sharing data that does not include all of an individual’s health data can be the source of errors and biases, as the data is not representative of a complete patient’s health pathway. Finally, if individuals’ data sources are error-prone, the derived datasets may also include errors, even with statistical corrections at population level.

We believe that ethical and truly solidaire data sharing in healthcare requires high-quality data, integrating all information of each individual into an interoperable and reusable longitudinal health record.

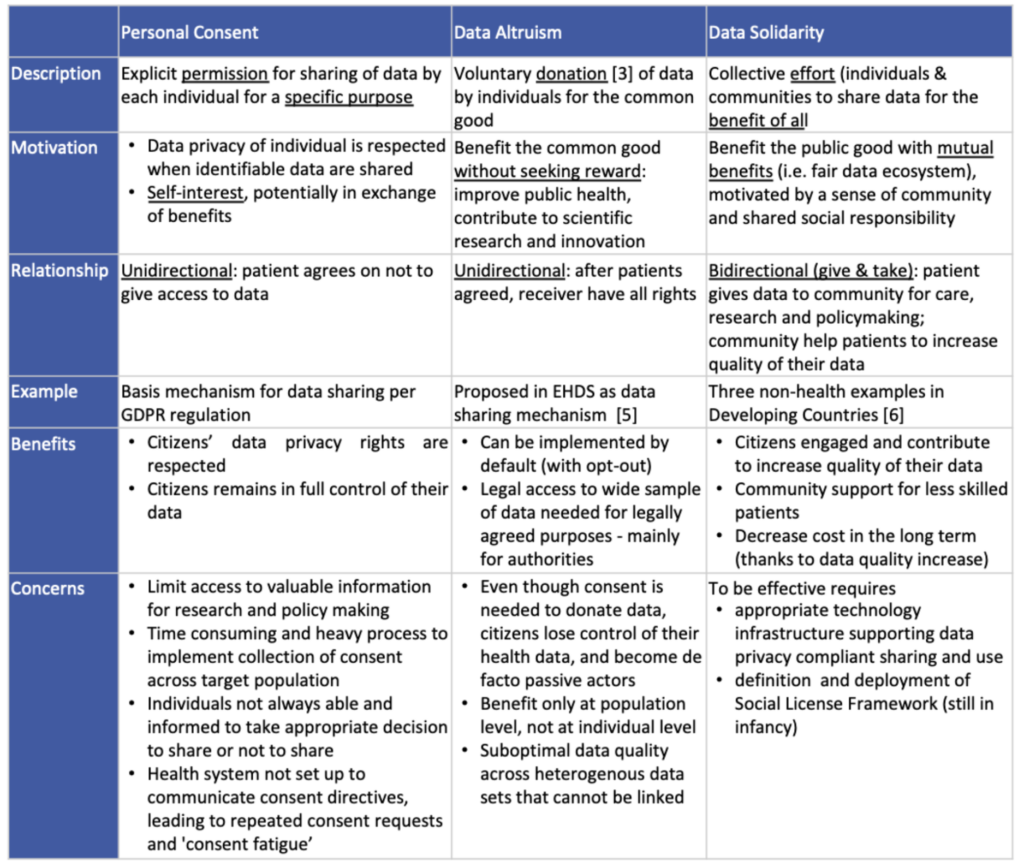

In this blog, we first compare three data sharing principles: Personal Informed Consent, as mandated by the GDPR regulation outside of legally approved purposes of public interest [2], Data Altruism defined in the DGA [3] and reused in the EHDS [4], and Data Solidarity building on symmetry in human digital agency supported by a Social License Framework combining personal informed consent and community engagement. As Data Solidarity appears the most equitable approach in a data greedy world, while maximizing respect of individuals’ data privacy and preferences, we expand on the components needed to support its effective implementation.

Comparing 3 principles of data sharing

The table below provides a comparison of the 3 most frequently mentioned mechanisms underlying data sharing.

We did not reference the Data Permit proposed in Article 46 of the EHDS as we do not consider it as a data sharing mechanism: it is required by law and the ‘power’ resides in the hands of the certified Health Data Access Bodies, i.e. public authorities allowed to request, access and process personal data for legally agreed purposes. Citizens are not asked to give their consent, although they have the option to opt-out and they can access a public website explaining how their personal information is used.

There is an increasing agreement that personal consent as the unique tool to secure human agency and individual rights is no longer acceptable in today’s data-driven era, as justified by the concerns identified in the table above. This led the EHDS authors to propose the Data Permit and Data Altruism, which both generate other concerns.

While Data Altruism and Data Solidarity promote the ethical and beneficial use of data, there are three main issues with Data Altruism1.

- The citizens lose control of their health data, and become de facto passive actors which is in direct violation with the core principle of empowerment of the EHDS to “support individuals to take control of their own health data”: once their data are donated, there is no incentive for citizens to further engage in their health data, and potentially in their health.

- There is no benefit at the individual level. While the whole population benefits from insights derived from donated data, there is no requirement for these insights to benefit the individuals who donated their data.

- It does not solve the issue of data quality and cost-effective data reuse. Data is typically donated in heterogeneous format and anonymized. While it can be transformed in the format needed for reuse – following the costly ‘curation many times, use once’ model [8] – as data is anonymized there is no possibility to link data on the same citizen across data sources and to provide a longitudinal view of the individual, so important in personalized medicine and integrated care.

Data solidarity emphasises cooperative efforts and the sharing of benefits between stakeholders. In a data-driven economy, this model is the most equitable and potentially the most cost-effective, provided it guarantees quality, interoperability and reusability of data, and respects data confidentiality and security. This requires symmetry in human digital agency, i.e. balance in power and influence among different stakeholders in managing (health) data, and implementation of a Social License Framework, combining personal consent and community engagement: both concepts are discussed in this blog.

Human digital agency and the need for Health Data Intermediaries

What is human digital agency

In sociology [9], human agency refers to the capacity of each individual to act independently and make their own choices based on their aptitude. It emphasizes the idea that individuals are not just passive products of society but can actively shape their own lives and the world around them through their actions and decisions. By extension, human digital (health) agency refers to the capacity of individuals to effectively use digital technologies to control their personal data, to make decisions and take actions influencing their self-care and to live healthy lives.

In our view, human digital agency includes the capacity of individuals to integrate and curate all their health data

into an high-quality, interoperable and reusable longitudinal health record, provided they have appropriate digital solutions.

One cannot expect all citizens to be knowledgeable in health and actively engaged in managing the quality, interoperability and reusability of their personal health data. The need for communication, training and education makes the ‘effective use of digital tools to control their data’ mentioned above, close to unachievable, unless software developers maximise the power of Intelligent Digital Assistants and adaptive human interfaces to hide the complexity of the tasks in the backend and deliver frontend applications which are simple, intuitive and adaptive to different literacy levels requiring limited/no training. If we can develop tools as simple as on-line banking (more than 90% penetration in Europe and 66% in the US [10]) we could hope for a smoother and quicker uptake of citizen-centric health data management digital solutions generating high quality, interoperable and reusable health records. Such solutions should form the backbone of Health Data Intermediaries.

Introduction to Health Data Intermediaries

The 2020 EU Strategy for data [11] introduces 4 pillars: 3 cross-sectorial ones (governance, infrastructure, skills) and sectors specific data spaces. Within the governance pillar, the Data Governance Act [4] applicable since September 2023 describes 2 approaches for data management: data intermediation services and Data Altruism organisations. The EHDS regulation [3] approved in May 2024 refers to Data Altruism, without mentioning data intermediation services for data exchange, be it in clinical care (primary use) or research/policy-making (secondary use).

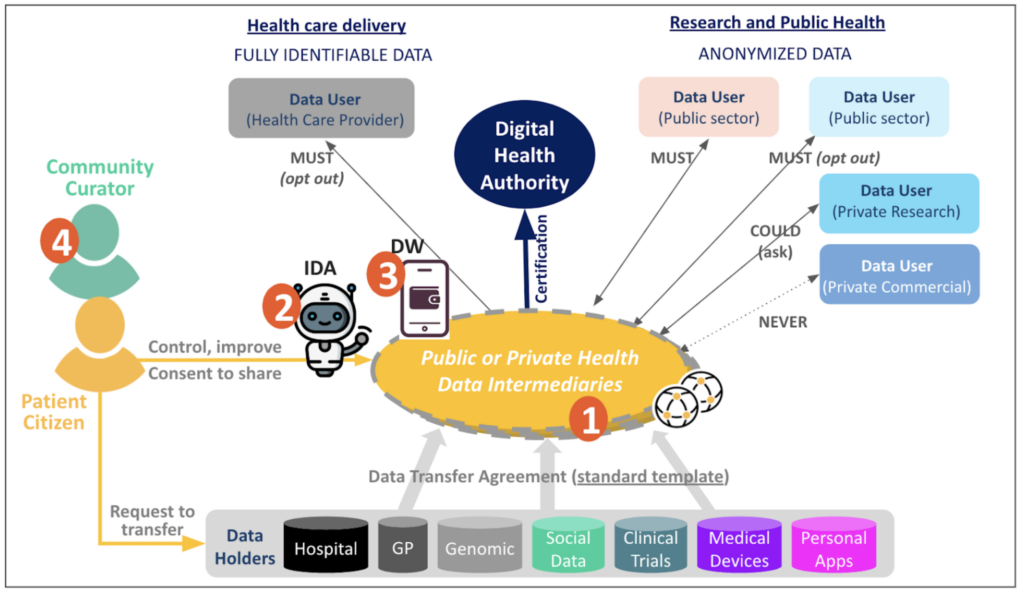

As explained in a previous blog on EHDS, we believe this is a missed opportunity that can still be rectified by introducing Health Data Intermediaries (HDIs) i.e organizations that serve, as trusted partners, citizens to manage (i) the pooling of their personal health scattered across multiple Data Holders, (ii) the integration, curation and quality enhancement of their data, and (iii) the sharing of their data based on individual’s preferences. HDIs would act de facto as Data Controllers on behalf of citizens, ensuring privacy, safeguarding personal data, and fully upholding data subjects’ rights such as the yet to be implemented Data Portability right.

HDI would need to be certified by the competent national Digital Health Authority, in the same way that National Contact Centers for Digital Health (NCDPH) are expected to be certified per the EHDS regulation. HDI could be private or public; NCDPH could be the public HDIs if they deploy a full fledged technology solution and social license as described below.

Sustainability and potential business models of Data Intermediaries are described in detail in an excellent review by JRC [12] and is not expanded further in this blog.

The MyData operators reference model [13] proposes 9 functional elements2 to support Data Intermediaries. Building on the experience of MyData emerging data operators and the AIDAVA Horizon project, we suggest providing these 9 functions through 4 components in the HDIs’ technology platforms.

- Data Intermediation Services – as regulated by the EU Data Governance Act – implements secure data exchange and sharing across health stakeholders with the consent of the individual. This is the core of the HDI services.

- An Intelligent Digital Assistant (IDA) supports integration and quality enhancement of individual personal health data and delivers an interoperable and reusable personal health record. HDIs should include such an IDA in their digital solution.

- A personal Digital Wallet (DW) manages citizens’ specialised personal datasets – such as IPS, vaccines credentials – and supports privacy compliant data sharing based on user preferences. HDIs should also include a DW in their digital solution.

- Authorities should develop the services of Community Curators, trained to help citizens who need it to manage their data and improve its quality. These services could be made accessible through the HDIs.

The first three components will be further described in our next blog dedicated to the digital solutions of Health Data Intermediaries. Availability of Community Curators is directly related to community engagement at the core of Data Solidarity and is detailed below.

Social License Framework

All citizens cannot be expected to be able or interested to properly manage their personal health data, even if provided with an intuitive, adaptive and intelligent digital solution. And yet, to ensure equitable care, all citizens must have access to personal data with the same level of quality, regardless of their level of digital literacy and health. That is why we need a Social License Framework to define how community curator services can be provided to citizens, while clarifying the conditions under which citizens can share their personal data with the community.

Community Curators

A Community Curator can be defined as a health community steward, responsible for supporting citizens in data curation and quality enhancement of their personal data. They could support citizens on demand, when they are not able to answer specific questions or they could completely take over responsibility for the individual’s health record. Community Curators would need to be trained to an adequate level of health and digital literacy; they should be able to contact the individuals they support to request specific personnel information unknown to them (e.g. date of a specific encounter missing in a dossier) and required for data quality enhancement.

The services of Community Curators should be part of the healthcare system framework and provided to everyone as a service if equity is to be achieved. Payment should be made in the same way as for any other social worker service.

Conditions of sharing

To move away from the current solutions that present an asymmetry of power in human digital agency (i.e. personal consent per GDPR, Data Donation per DGA and Data Permit and Data Altruism per EHDS), and to ensure equitable care as well as benefits for all health stakeholders, the conditions of data sharing need to be specified and formally agreed. Although a consensus must be reached, we propose the following as a starting point.

- Conditions enabling citizens and patients to increase the quality of their individual data, with adequate means such as the HDIs and community curators.

- Conditions of ‘MUST share, always’ to legally authorized data users. Sharing should take place without personal consent and without opt-out possibility; shared data should be fully anonymized. This should be limited to Public Health Emergencies of International Concerns (PHEIC) defined by the WHO.

- Conditions of ‘MUST share, by default’ to legally authorized (e.g. authorities) and predefined list of agreed data users (e.g. specified list of healthcare providers). Sharing should take place without personal consent while opt-out should be possible. Shared data should typically be anonymized, except for well defined purposes such as clinical care where data should be fully identifiable.

- Conditions of ‘COULD share’ to certain types of data users (such a private research organisation). Sharing should only take place after obtaining the explicit personal consent of the user, based on a request clearly specifying the purpose for which the data is to be used. Shared data should typically be anonymized, unless specifically requested otherwise.

- Conditions of ‘DO NOT share’ should also be defined to ensure data privacy and security of citizens more easily influenced to share data, for instance by social media, or less able citizens.

- All other cases should be under the discretion of each citizen through personal consent.

Social Licence Framework

Verhulst in ‘Responsible Data Re-use in Developing Countries’ [6] describes a Social License Framework, in which individual consent is complemented with community engagement to ensure that data initiatives are ethical and equitable across all stakeholders. Community engagement should go further than what was defined in 2022 by the Canadian team [14] in a ‘Health Social License’ that specifies data-related activities that have the support of members of the public, and under what conditions.

The Social License included in the framework can either be an official contract that details the needs, expectations, and conditions of parties involved, or an informal agreement that captures the collective consent of the stakeholders. In the context of data sharing and reuse, this includes an approved set of best practices involved in pooling, cleaning, sharing, and utilizing data. It typically entails agreement of individuals to participate in the community by sharing high quality data, engagement of all stakeholders and most specifically community curators supporting the individuals whenever relevant to increase the quality of personal health data, transparency on the way data is used in an accountable way and fundamentally building trust and legitimacy of ethical use of data for the benefit of all [15] .

There is little experience in implementing Social License Framework; the work around RRI-SSH [16] and identification on best practices in the Data Tank [17] should lay the ground for further developement and deployment.

How to implement data solidarity in EHDS ?

As EHDS is the topic of many conversations in Europe, it is difficult to close this blog without asking how data solidarity could be implemented in EHDS and make the current regulation a true game changer for healthcare.

First and foremost, the healthcare community as a whole needs to realize the critical necessity of having high quality health data for each individual to enable good clinical care at individual level, the main objective of healthcare systems. In addition, the quality of population level data (which summarises the key data from individual patients’ data) relies fully on that individual patient data quality.

Authorities are responsible for the welfare of the population,

which they monitor with high level data summarised at population level, not with individual patient data.

Managing patient data at individual level is a shared responsibility across all healthcare stakeholders, including the patient.

The second focus should be on accelerated deployment of full fledged HDIs either as a public organisation, by extending the technology infrastructure of regional and national NCDPHs, or as a private organisation. The IT researcher community should expand efforts on intelligent and intuitive virtual assistants supporting individuals in managing their data. Authorities should foster the deployment of HDIs digital solutions by accelerating development and enforcement of standard data sharing agreements, by expanding existing efforts on digital wallet deployment and use, and by considering incentive models for individual patients and organisations sharing high quality data and finally by developing training programs on digital health for citizens but most specifically for community curators. Healthcare staff also have the responsibility of introducing the use and benefits of data intermediaries to patients, for their clinical care and health monitoring.

The third emphasis should be on adapting the Data Permit proposed in the EHDS and agreeing on different data sharing mechanisms, based on the context and defined in a Social License Framework. This should also include the description and conditions of Community Curators services.

Conclusions and next steps

Effective data solidarity requires symmetry in human digital agency and a social license aiming at maintaining a high-quality, interoperable and reusable longitudinal health record for each individual, to allow patients and citizens the clinical care they deserve while supporting learning health care systems. Whether that is achieved through changes to the data infrastructure of public services or market provided health data intermediary services – both supported by an innovative technology platform including intelligent digital assistants and personal digital wallet – is likely a regional question. It needs further research to elaborate the social license concepts.

This approach would allow an innovative, more cost-effective implementation of the EHDS regulation, moving away from the obsolete, public-health centric view envisioned currently and opening the space for a true FAIR data economy for the benefit of all stakeholders.

1 An interesting concept that would deserve a full blog and is not further explored in this blog is posthumous data donation [7]

2 includes: Identity management (IM), Permission management (PM), Service management (SM), Value exchange (VE), Data model management (DMM), Personal data transfer (PDT), Personal data storage (PDS), Governance support (GS) and Logging and accountability (LA)

How Can I Find Out More and Participate?

- Join MyData Global as a member

- Join MyData Slack and discussions at the #health-data channel

- Follow MyData Global LinkedIn and X feeds

- Subscribe to our newsletter

- Sign the MyData Declaration

Acknowledgements. The ideas described in this paper were inspired by the principles of human-centric use of personal data, the DNA of the MyData Global organisation, and by the very intense discussions on the potential use of MyData operators framework within the #health-data community. Kristof Vanfraechem CEO DataForPatients, Eric Sutherland Senior Health Economist at OECD, Don Willison Adjunct Professor at the Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation University of Toronto and Dr. Peter Janes CEO Abdagon AG provided many insightful comments.

This post is co-authored by Isabelle de Zegher (MD, MSc), currently serving as the vice-chair of MyData Global’s Steering Committee and clinical coordinator of the AIDAVA Horizon Europe project and Fredrik Linden co-founder MyData Sweden and Vice President of Business Development iGrant.io.

References

[1] B. Wawrzyniak, “The interplay between data-related harm and the secondary use of health data,” Canvas. Accessed: Aug. 15, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://medium.com/odi-research/the-interplay-between-data-related-harm-and-the-secondary-use-of-health-data-09ffd59f7cf0

[2] “Regulation – 2016/679 – EN – gdpr – EUR-Lex.” Accessed: Aug. 06, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj

[3] “European Data Governance Act,” Shaping Europe’s digital future. Accessed: Aug. 06, 2024. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/data-governance-act

[4] “European Health Data Space,” Public Health. Accessed: Aug. 06, 2024. https://health.ec.europa.eu/ehealth-digital-health-and-care/european-health-data-space_en

[5] M. Nurmi, “TEHDAS’ proposals for promoting Data Altruism in the EHDS,” Tehdas. Accessed: Aug. 04, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://tehdas.eu/tehdas1/results/tehdas-proposals-for-promoting-data-altruism-in-the-ehds/

[6] “Responsible Data Re-use in Developing Countries: Social Licence through Public Engagement.” Accessed: Aug. 04, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.afd.fr/en/ressources/responsible-data-re-use-developing-countries-social-licence-through-public-engagement

[7] E. Harbinja, “Posthumous Medical Data Donation: The Case for a Legal Framework,” in The Ethics of Medical Data Donation [Internet], Springer, 2019.

[8] I. de Zegher et al., “Artificial intelligence based data curation: enabling a patient-centric European health data space,” Front. Med., vol. 11, p. 1365501, May 2024.

[9] “In sociology, what does ‘human agency’ mean?,” Quora. Accessed: Aug. 04, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.quora.com/In-sociology-what-does-human-agency-mean

[10] “Website.” [Online]. Available: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1228757/online-banking-users-worldwide/

[11] “EUR-Lex – 52020DC0066 – EN – EUR-Lex.” Accessed: Aug. 30, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52020DC0066

[12] M. Micheli, E. Farrell, S. B. Carballa, S. M. Posada, S. Signorelli, and M. Vespe, Mapping the landscape of data intermediaries. 2023.

[13] “Understanding MyData Operators.” Accessed: Aug. 04, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://mydata.org/publication/understanding-mydata-operators/

[14] “Social Licence Report,” HDRN Canada. Accessed: Aug. 15, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.hdrn.ca/en/public/public-resources/reports/social-licence-report/

[15] “The Urgent Need to Reimagine Data Consent.” Accessed: Aug. 05, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://ssir.org/articles/entry/the_urgent_need_to_reimagine_data_consent

[16] K. Schuch, “Proceedings of the Conference: ‘Impact of Social Sciences and Humanities for a European Research Agenda – Valuation of SSH in mission-oriented research’ VIENNA 2018,” no. 48, p. 216, Jul. 2019.

[17] “Social License Lab – The Data Tank,” The Data Tank – Serving the common good together, by using data differently. Accessed: Aug. 06, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://datatank.org/social-license-lab/